On instincts...

The spring before I turned 21, I studied for a semester as an exchange student in Copenhagen, Denmark. I could have never anticipated how much the 4-month trip would continue to have an impact on my life. Years later, it would inspire a 15-month move abroad to work internationally, and it would teach me the simultaneous discomfort and thrill of embracing opportunities that seem daunting at first. When you're starting life over in a foreign city, you start to appreciate the power of small successes: finally getting your work visa from the government even though the entire Danish government is on summer vacation, getting your first paycheck because said visa went through, and getting a phone plan so you can text the friends you haven't yet made. Each small triumph is empowering and worth celebrating. Soon, strangers start to feel like family and you're a regular at the local bakery.

Similar to establishing yourself in a foreign country, learning the ropes of the professional kitchen can be an intimidating journey. Every kitchen has its own systems, language, etiquette, and culture. That being said, it is key to remember that every day is filled with small successes if you take a step back and let yourself recognize them. Day after day, you practice your craft and you start to develop the instincts and intuition of a chef. You start to gain the ability to anticipate challenges before they happen, multi-tasking kitchen projects becomes second nature, and your internal sense of timing improves with each day. Those instincts become a part of you-- how you think, how you move, and how incredibly heat-resistant your fingertips become.

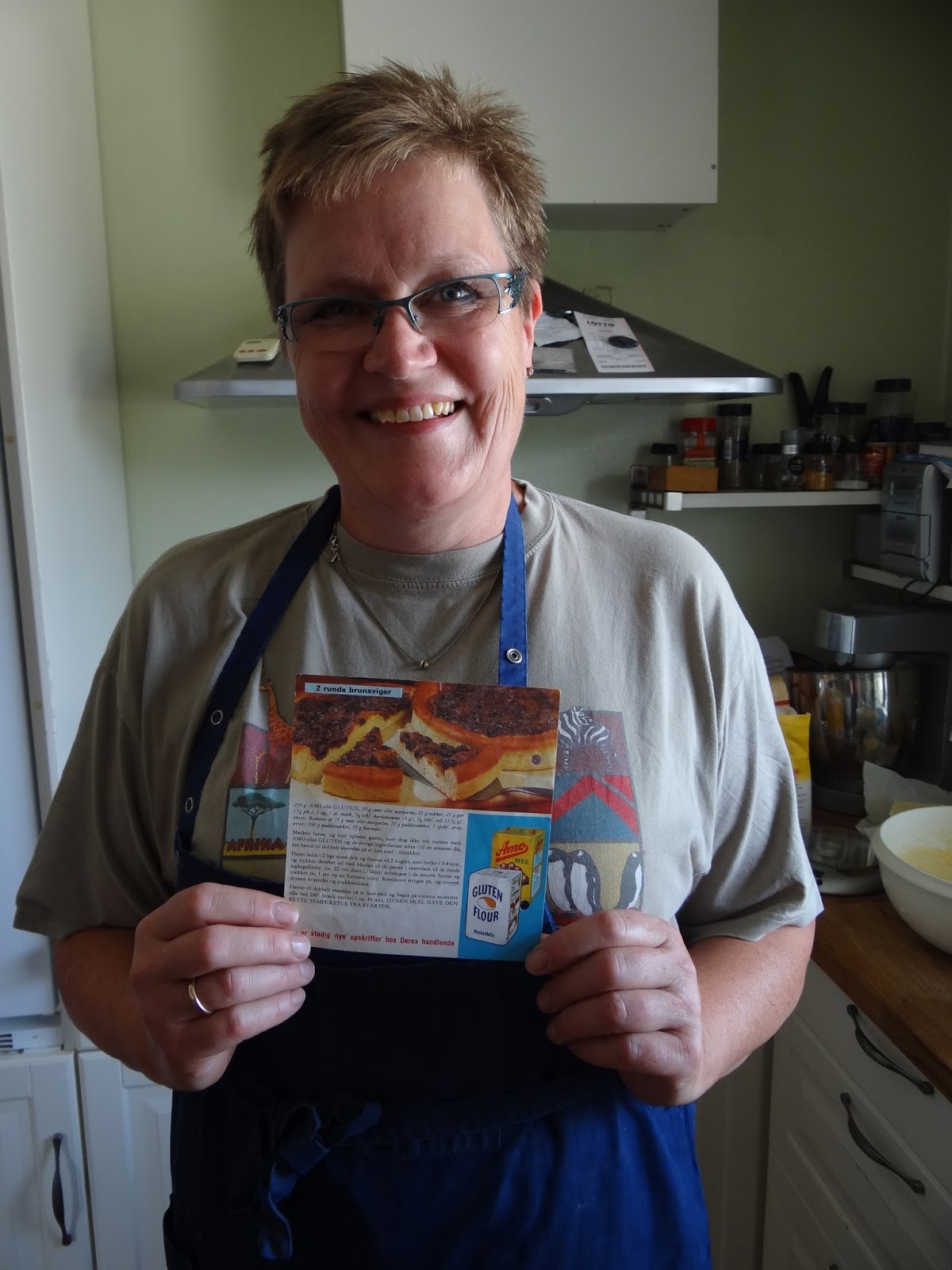

Reflecting back on my time as a wide-eyed exchange student, I had a fortuitous housing placement with a host family whose matriarch, Lone, is an excellent chef. I'm still not sure how we were so perfectly matched, but perhaps I mentioned something on my housing form about being excited to try Danish pastries.

In any case, so began a long friendship across continents. Lone was nice enough to cook for me and with me, and during one lesson she taught me how to work with yeast. She told me to feel the water to see if it was the right temperature: too cold and the yeast would not activate, too hot and the yeast would die. I started to look for a thermometer, but she corrected me. With her chef instincts clearly developed, she no longer needed a thermometer to check...she knew exactly what it should feel like. "Feel the water", she instructed me. "Over time, you will start to learn." I still appreciate the certainty that a good thermometer can give you. But now I understand the importance of what she was getting at all those years ago: our instincts are one of our most valuable tools in the kitchen.

Recommended reading: In the spirit of kitchen instincts, the New York Times Food section did a series this month on how to become a better cook using your senses. Check it out: To Become a Better Cook, Sharpen Your Senses